(Deccan Herald) Are women writers an easy commodity or a dangerous liability?

- Meena Kandasamy

- May 18, 2024

- 4 min read

In March 2020, I came to Delhi to write about the anti-Muslim violence unleashed on its streets in the wake of the citizenship protests. Walking with Ruchira Gupta and other activists through the affected areas and visiting relief camps, I made a silent promise to myself: I will move back. It was desperate prayer too. I had spent close to a decade living abroad but having seen what I'd just seen the starkest image was the fluttering wings of a pigeon in flight outlined in white against the pitch black backdrop of a mosque bombed by Molotov cocktails — I wanted to stay in India and fight the rising fascism. Screaming from the liberal West gave me the illusion of freedom and safety — but being here mattered. I left for London the day before the borders closed. When the second lockdown happened in late 2020, I moved back to India with my two kids (one was a toddler, the other was an infant who was still being breastfed). I did not make too many plans, and I was not even aware how daunting the task of single parenting such small children would be. I was confident that I would figure out everything eventually; I wanted to take it one day at a time.

There is something about motherhood, especially handling very small children single-handedly, that affects the nature of what you can do as a writer. Children's needs are immediate, the attention they demand cannot be postponed to another part of the day. I learnt that time to write as a mother only came to me in snatches. It is the equivalent of having an affair, you learn to make the best possible use of stolen time. I could handle a poem as a single unit, I did not have the luxury of days, months, years which a novel demanded. I decided to dust this old project — translating the Thirukkural — and worked on it. The kurals were two lines of poetry, even if I finished perfecting one in the craziness of an afternoon, it felt like an achievement.

The next book which I worked on upon coming here, and trying to settle into Puducherry, was Varavara Rao's poetry. Working on this project with N Venugopal was an enriching experience; I got to work up close with the entire body of Varavara Rao's poetry which spanned a period of more than six decades. It felt like I was looking at the alternate history of post-independence India, written by the rebel poet.

The selections had to represent him, the evolution of his voice and his political trajectory (which to be honest is extremely consistent) — but they also had to represent what was happening around him. When I edited his poems, I realised the love and admiration that it takes to handle a poet's lifetime of work. We also worked with a tragic urgency — Varavara Rao was still in jail, his health was failing, and he was in and out of hospitals. I wanted him to hold a copy of the book; the obstacles we faced were nothing in the face of what he had withstood.

Around the same time, I was also in touch with Comrade Vasantha, the wife of Delhi University professor GN Saibaba. He was in solitary confinement in the Nagpur prison (he was eventually acquitted of all charges after being incarcerated for a decade), and I was asked to write an introduction and help find a publisher for the volume. That book was eventually released as Why Do You Fear My Way So Much.

Looking at the poems of these dissident stalwarts, in some strange way, made me take a fresh look at my own work. I always believed that I'd firmly shut the door on being this poet-persona. In my mind, I thought that Ms Militancy was an angry young woman's manifesto — I had outgrown that age. I wanted to do things which required sophistication, patience and absolute grace — writing fiction; growing my nails; being a thug mum. Because I wrote so much else after Ms Militancy, I never looked at poetry as the mainstay of what I did. So, when I set about retrieving all the poems I'd written in the last decade, I was quite surprised. There were a lot of poems, and they'd all been written at some specific juncture, as a response to something that was happening (the pandemic, the rape in Hathras, the citizenship laws, caste atrocities, honour killings). There was this, there were so many love poems and there were also poems about the space/role of poetry.

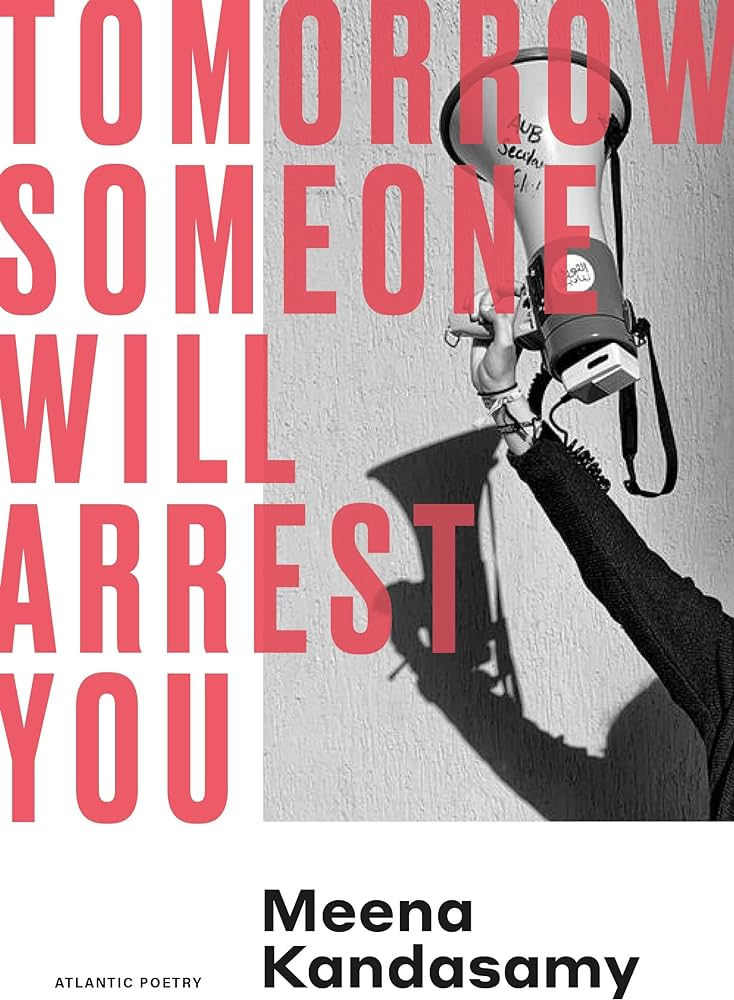

And that is how Tomorrow Someone Will Arrest You came into being. Being considered a political poet comes with a lot of baggage, especially in a society which wants to outsource all its political intellectualism to men. As a woman who writes poetry, you are an easier commodity to handle when you are crying about a long-ago heartbreak; you are a dangerous liability when you are a critic of the regime. A publisher declined to distribute my book in India citing legal risks. Patriarchy is insane; its impulses to shun and control women take myriad forms.

Friends often ask me why I'm not arrested yet, given that much of my writing would offend the sentiments of those who are opposed to the slightest murmur of criticism. Some of them tell me that it is the (gendered) optics of the operation which keep me safe — a young mother being hauled to jail would reflect badly on a regime which has earned a worldwide bad rep for curtailing free speech. Others tell me, you are a woman, so they will not take you seriously!

Sometimes, sitting in front of a screen, on a night like this, I think that's what all of this life of a woman writer is — this endless scream into the void to be taken seriously.

Your blog always provides high-quality content that is both informative and engaging! The structured format makes it easy to follow, and the depth of research ensures credibility. Your writing style is clear and concise, making complex topics easy to understand. The effort you put into crafting valuable content is truly commendable. Keep up the great work! I will definitely continue following your blog for more insightful and well-researched articles.

Java Burn Reviews

Java Burn Coffee Reviews

Puravive Reviews

Liv Pure Reviews

LeanBiome Reviews

Sugar Defender Reviews

Sugar Defender 24 Reviews

Nagano Tonic Reviews